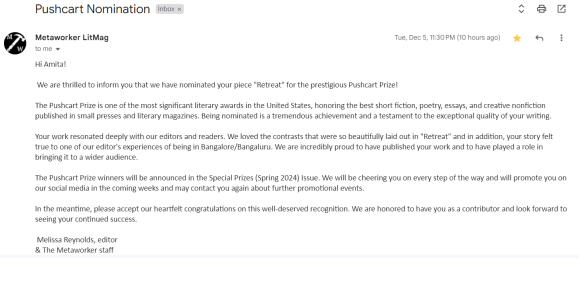

Originally published April 2021 in Down in the Dirt Vol. 186, anthologised and available in print on Amazon; republished in June 2022 on Bookends Review.

[Image: Image: stills from Tehching Hsieh’s performance-art piece, where he signed in to a clock every hour, night and day, every day for a year.]

1321. Lunchtime. But this P2WM5 is due 1500. No time for a sit-down. J1N1 sends in sandwiches. I doff my heels, unbutton my collar, and eat at my picture-window.

My last promotion, they were surprised when I chose this 5th-floor office. A non-corner-office, furniture outmoded, and so low. I said: ‘I have acrophobia.’

I couldn’t say: ‘I want to look, one last year, out of the eyes of the beast.’ This picture-window looks into the slum across the road.

The men are coming home for lunch. From where? From that corner. Beyond that corner my picture-window doesn’t see. The men are mostly autorickshaw-drivers.

Some of the young men, who’ve acquired broken English, work as shop-assistants. They don’t come home for lunch. I see them out my tinted windows on my way home.

The children trip down the potholed lanes to welcome their fathers home, excited, as if they’ve been parted all fiscal quarter.

The women rushed home earlier to cook lunch. I watched them streaming in, 1216-1249. From where? From that corner. The women are mostly domestic servants.

Some of the young women, who’ve put themselves through college, work in government-offices. They don’t come home for lunch.

The slum-people have no collars to unbutton, no heels to kick off: at work and at home, they’re slipper-shod. (Except the children, who’re barefoot.) At work the autorickshaw-drivers’ khaki shirts are already half-unbuttoned. The women keep their work-saris on to cook, eat, sleep. I suppose, when you can’t afford work-clothes separate from life-clothes, you cope.

They haven’t clocks, either. How do they know when it’s lunchtime? They know because other people come home for lunch. But how do those people know? Their stomachs know. Slum-people haven’t disciplined their stomachs. That’s why they’re slum-people.

Alarm. Must finish the P2WM5. J1N1 sends in more coffee.

1432. I’ve had so much coffee I’m half-nauseous, half-scatterbrained. Still I can’t focus. I’ve tried caffeine-pills, stretch-breaks, and various productivity-maximising podcast-playlists. I jump up for another picture-window-break.

The women sit together, making – some kind of sweets. They’ve established an assembly-line! Clever. One woman stirs a cauldron; another spreads the contents out to cool; some roll the contents into balls; others press the balls into moulds.

So: some festival’s approaching. Which?

What’s today’s date? J1N1 says: 12-11-20. Are we on US date format, or Indian? Is today 12 Nov, or Dec 11? I never track what date it is. J1N1 always tells me: ‘Parimeeta, do this next.’

The women sit under – some kind of tree. For shade?

What’s today’s temperature? I lean against the windowpane. The glass feels the same cool as always. Temperature optimised for productivity, and held constant, for constancy optimises productivity.

An assembly-line has one drawback. With each person doing her own work alone, everyone will seek shortcuts. Minus a supervisor, how d’you whom to fire when something goes wrong? Alarm. End of sightseeing-break.

1453. My P2WM5 is done. They’ve revamped the intranet dashboard. How do I submit my work? I remember this morning’s memo from Technical – I flagged it to read later and now I can’t find it. Shit, which button do I press?

Here! Submitted.

I want to email Technical: ‘Why d’you keep changing a dashboard that works fine?’ I don’t. Designing the dashboard is their job. My job is using it. I find the memo and read it and practise navigating the new dashboard. I archive the email in my Technical folder.

1554. The TX2KR, greenlit 10-11-20, has come through Redesign for me to review. I have – J1N1 highlights Parimeeta’s Calendar to show how long Parimeeta has – six working days. J1N1 highlights the rest of today – ah, so today’s Friday – and then all of next week.

I used to be able to tell the days by my coffee intake. Each office used to have a coffee-machine. I was going through one 500g pouch of instant coffee a week, rubbishing the packet every – that’s when I knew it was – Friday. They’ve taken away the coffee-machines and now J1N1 sends in coffee-cups every half-hour. So now I can’t tell the day by coffee. But now I can tell the hour. Well: I can tell that another hour has passed.

How much coffee do I go through a week now? J1N1 knows. J1N1 measures my hours.

How much coffee do the slum-people drink? Look at them, making sweets, washing their autos and motor-scooters, so energetic though they’re in the sun, so enthusiastic though they’ve nothing to look forward to. I read that 91% of people born in the slums die in the slums.

Nilambita texts: “Prithak confirmed for drinks. Shall we meet 1930, Yavolter’s?”

I reply: “See you there.”

Nilambita’s my classmate from Std. XI-XII. Prithak’s my batchmate from McCann’s, ’04-’06. Now they’re both here, in Bangalore, doing – something. We’re just friends. We unbutton our collars, drink, and discuss anything but work.

I don’t even know what Mom does for work. Or my boyfriend. I know they work in corner-offices, temperature and lighting optimised, cheered on by coffee, alarms, and their own personal J1N1s.

1813. Picture-window. Don’t worry: I’m working, in my head, on the TX2KR. The men are coming home again. Some children hide until their fathers pass. Other children skip out in a welcome-party. Didn’t they just meet a few hours ago, or have I lost all count of the hours? Some children take their fathers’ hands and ask how their day went. Isn’t every day the same?

1843. Picture-window. The children approach their family vehicles. Auto-rickshaws, delivery-vans, secondhand motor-scooters, and the water-tankers that correct for a steep price shortages in the civic water-supply. Apparently there’s a drought on, on the other side of my picture-window.

In garish polyester lace-and-net finery, brandishing garish plastic streamers, but still barefoot, the children decorate their family vehicles. I remember, from when I was a child, occasionally unoccupied, some festival where some Indians decorate some work implements. So this vehicle-decorating, sweet-making festival, is in – Month#11, or #12? And it’s called – what?

If my picture-window were openable, the slum-people’s voices would float across the street up to me. I’d catch the festival’s name. I’d smell those bucket-shaped scarlet flowers, those spray-shaped ivory flowers, that blossom this time of year over the festive congregation. I’d feel how hot it is this time of day, this time of year. 1851 12-11-20.

Oh forget them and their festival. They’re just sightseeing life. Their lives are a procession of meal-times and homecoming-times and festival-times. They’ll never be anyone. And I’m sightseeing them, but only in the breaks of my, shit, workday. 1900. Alarm. End of workday.

The slum-people drink no coffee. They’ve got other things to keep them up. Bosses shouting. Children screaming all in one room. Hunger-pangs at midnight. The seasons, which they can tell without calendars. Flowers and festivals, whose names they know.

I turn away and decide I’m graduating from coffee to something stronger. I’m graduating out of all contact with the hours of the day.

Another promotion is approaching. This time I’ll choose a windowless office. Move up some floors and into the belly of the beast. Commit to my future. For us, this rite-of-passage. I draw the shutters down my picture-window and stride away and behind me my office auto-darkens.