What I Read:

Almost No Memory: I’m reading Lydia Davis’s short story collections in chronological order; this is her second, published in 1997. Lydia Davis is very easy to read: every sentence is concrete, there are very few backs-and-forths in time, most stories are in first-person and there are seldom any character names to remember, and the meaning seems to lie close to the surface in an appealingly refreshing themeless way. But after reading a few in a sitting, these stories begin to grate on me: without a careful reading, they can seem insubstantial: like the art of writing itself, the art of reading Lydia Davis is easy to learn but hard to master. Her apparently transparent stories reward close reading.

The emotional landscape of these stories is often understated to the point of seeming absent, the stories a bald statement of events unconnected by the silver thread of emotion, which makes meaning. But the emotion’s there alright: some of her stories reference visits to therapists, which helps the reader identify a sort of flattened affect typical of depressives.

Davis’s eye for observation is phenomenal. She has a quiet relish for ordinary life. A walk around the neighbourhood that a mother takes with her infant in a pram seems pregnant with meaning; a young English professor who daydreams of marrying a cowboy even after finding a more suitable mate invites us, without one sentence of rumination, to examine our own incongruous daydreams; the fate of cats in a prison signals the advent of new, more efficient, and perhaps not better governance; stories about writing stories make us question what it is that makes a story: what pieces of real life or fancy do and don’t belong in a story?

Apropos, most of Davis’s stories defy conventional narrative structure. Things happen, often a lot of things, but they’re not linked together by a clear arc or singular point of tension. In the long story “Lord Royston’s Tour,” a nineteenth-century Englishman sets out on a tour of the Continent and traverses Russia, collecting bits of local news and culture like a magpie. There is no comment on his inner life, his responses, or his desires; after escaping many close shaves with the cold, sickness, and brigands, he dies abruptly. This story isn’t intended as a travelogue: it’s too spare in its details for that: nor does it paint a portrait of Lord Royston, who in the story is only ever referred to as ‘he.’ The only point I can discern in this story is that human life was cheap back then, and a nobleman who was sightseeing the world as something that happens to other people eventually succumbs to the same phenomenon. Yet even this story is, frustratingly (to me as I try to figure out why), compulsively readable.

Some stories do explicitly invite musing. E.g. “Pastor Elaine’s Newsletter” asks us to consider how we treat each other, and warns us of the risk of accidentally training our children to be hard-hearted. “Almost No Memory,” portrays a woman who’s very brilliant and accomplished, and who has written shelves full of notebooks, but has almost no memory. Is this juxtaposition possible, we wonder. How can someone excel at their work, or keep track of their own sentences, or enjoy the act of reading, if they’re incapable of forming memories?

My favourite story is “The House Behind,” set in Paris. Scene: the two houses surrounding a courtyard, with the street-facing house and the backwards-looking house (‘the house behind’). These two flat complexes are inhabited by prosperous and poor inhabitants respectively. A random act of violence sparks a cold war, following which interhouse relations deteriorate drastically, and the personalities of the front-house dwellers diverge markedly from those of the back-house dwellers. This is not an allegory: it reads always like a true story which happens to comment on class as an influence on the human psyche. This story features lifelike characters, though only in outline – unlike most of Davis’s pieces, which seem written from the author’s own persona, their interest revolving around minute observation of strictly delineated areas of human emotion. “Examples of Confusion” is another gem: a series of tiny but wonderfully observed incidents involving mental confusion. The vignettes cohere into a story by populating the phenomenological set of all possible ways to feel confused.

Lydia Davis is an interesting writer: easy to read, hard to analyse. Her writing is compelling but I can’t say why. Perhaps I shall try some pastiches and learn that way.

The Sound & the Fury: Faulkner’s 1929 masterpiece butted into my reading list, I confess, through a list of 100 Greatest 20th-Century Novels, as I scramble on the threshold of middle age as a lifelong aspiring writer to fill in chasm-sized gaps in my knowledge of contemporary literature. Back in school I’d read some of Faulkner’s short stories, but I’ve forgotten them so I came to S&F fresh.

The novel is divided into four parts, three of them set within days of each other in 1928 (with flashbacks to 1910) in a family home in the American South. Part One is narrated by Benjy/Maury Compson, a man in his mid-30s who is severely mentally retarded and cannot speak – though he seems to have excellent memory as well as an intuitive understanding of the emotions and conflicts tearing his family apart. Part One often reads as repetitive, as various family members at various time-points discuss who will watch Benjy, their grandmother’s death, the curse hanging over the family, and playtime. Benjy does however conjure some interesting effects via the impressionistic juxtaposition of facts:

“The room went away [when the light was switched off], but I didn’t hush [Benjy keeps crying], and the room came back and Dilsey came and sat on the bed, looking at me… She went away. There wasn’t anything in the door. Then Caddy was in it.”

“The kitchen was dark. The trees were black on the sky. Dan [the dog] came waddling out from under the steps and chewed my ankle. I went around the kitchen, where the moon was. Dan came scuffling along, into the moon”

“The flower tree by the parlour window wasn’t dark, but the thick trees were. The grass was buzzing in the moonlight where my shadow walked on the grass.”

It’s hard to get much of a sense of anything from Part One, but a few facts are established: Mrs. Compson is an invalid or fancies herself one; Caddy, Benjy’s sister, is attached to Benjy whereas some other members of the white family and their black household tease him; and black matriarch Dilsey is the family’s mainstay.

Part Two is narrated by Quentin and follows events on the day leading up to his suicidal mission. Quentin is the family’s star child: his parents sold off his idiot brother Benjy’s birthright to send him to Harvard, which disturbs Quentin himself. Deeply attached to his sister Caddy, Quentin narrates how he discovered what’s wrong with her, and how he failed to put things right according to his own notions of southern gentlemanly honour. An intensely sensitive young man, Quentin narrates his part of the story much more clearly, though his focus is on feelings and impressions rather than facts. Through him we get a clear portrait of the patriarch, a retiring but wise minister of the church, who appears to be an atheist with strikingly modern views on sex. Quentin is devastated by what Caddy’s choices in life have done to her, and is desperate to help. Fellow southerners make misogynistic remarks but treat him tenderly, which whets his fury. Finally he embarks on what sounds like a duel he knows he will lose: and so, after Mr. and Mrs. Compson have lost Caddy to her disgrace, they will lose Quentin to suicide.

Part Three is narrated by Jason, the youngest son, his mother’s favourite: a hardheaded brute of a man who is obsessed with money and what remains of the family’s honour. He keeps reminding his family that he’s their sole provider, but what he demands in exchange he is unable to obtain. Jason’s part is very factual and grounded, and the reader picks up a number of facts about the fortunes of the family. When Caddy’s planned marriage was broken off due to her prior affair with another man, Jason lost the job in a bank that had been promised to him; he works now, in bitter mood and with caustic tongue, at an agricultural goods store. Jason has a giant chip on his shoulder as the patriarch of a once genteel landowning family: he drives friends and family alike away from himself. Part Three raises questions about the ‘blood’ that runs in a family: the younger generation of the Compsons is repeating some of the same errors as the older, and one wonders whether it really was, as Mrs. Compson accuses, lack of parental supervision that caused this, or a ‘strain’ in the blood.

Part Four is narrated by a third-person narrator who mostly follows Dilsey, the loyal, loving head-servant. The lush, even baroque style here contrasts sharply with the impoverished style of Part One as events in the Compson family come to a head and it faces yet another disaster.

The Sound and Fury is a masterclass in using style to convey character. Parts One, Two, and Three paint compelling portraits of Benjy, Quentin, and Jason Compson: three brothers with very different outlooks (though clearly Jason and Mrs. Compson are the misfits in the family overall). The four parts could very well have been written by four different writers. The story the four parts cohere to tell is one of decline and loss, pride and lies, and above all of suffering. Benjy, confined in the yard, hangs on the fence leering at girls, dashes out the gate one day, and is neutered; Caddy confides her secret in Quentin and the only solution he can offer is to kill them both; Quentin does his best to shield his beloved sister from reality but cannot even shield himself; Jason works for years, thieving from Caddy, but loses his money and cannot recover it; and it is the innocent Benjy and his already disgruntled caretaker Luster who suffer the consequences. This book took me a while to get into, but from the middle of the second part on it compelled me. I’m told it’s a book that rewards multiple rereadings. While waiting for that time, I’ll explore Faulkner’s other work.

A few chapters of Godel, Escher, Bach: This 1979 landmark text by Douglas Hofstadter bumped its way into my reading list when I met an old colleague from my cognitive science days. I read a few chapters with great interest. I’ve not done maths since high school, and I did it only sparingly then, and my brain has grown away from logical thinking, many kinds of abstract thinking, and also struggles with linear thinking even in storytelling. GEB was bracingly challenging, but I soon got into the lingo of formal systems. Hofstadter’s range of subject is striking, his explanations lucid, his ability to explain complex concepts admirable. I am, however, abandoning this book, perhaps forever: the list of things I need to read to become a better fiction writer grows, I’ve recently begun skimming the news at least occasionally, and I have scant time to read anything else.

In the last few months I’ve also watched some films:

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1999) I watched because I’m a Johnny Depp fan. Depp plays his trademark of loveable weirdo: a 19th-century American police detective, a forensic pioneer with a phobia of blood. He wanders into a tale of murder and fearsome prophecies, has his heart snagged by what is apparently the villainess, and reasons his way out of the jungle of illusion. A charming little story, and the violence being mostly offscreen, the effects still hold up.

I’d read the screenplay of American Beauty (1999) years ago, and it stuck in my mind, especially the vision of a middle-aged man rejuvenated by the desire to win a young girl’s heart; the imagery of rose petals as symbolising the girl’s contrasting traits of seductiveness and innocence struck me too. I’d not watched any Kevin Spacey films before this; fortunately I found myself able to watch this despite having heard of his sexual misconduct. It’s a lovely film, framed by the protagonist narrating: ‘Today’s the day I die.’ Mena Suvari is perfect as the ingenue who pretends to worldly knowledge she does not possess; the Henry Cavill-lookalike is fine as the young man with a repressive father who has become sociopathic in the ease and gratuitousness of his lies; Annette Bening as the housewife with a stick up her behind who finds liberation with the poster-boy real-estate salesman provides comedic relief in a film that is already a disarming mix of comedy and drama. The magic realist sequences involving Lester’s dreams of Angela, and the exotic music that accompanies these sequences, captures the film’s pathos and magic. The storyline of the repressed homosexual, which unfolds abruptly, may be cliched by now, but perhaps it was new in its day.

I watched The Fighter (2010) and Ford v. Ferrari (2019) some months ago because I’m also a Christian Bale fan. I enjoyed both films, but at this distance all I can say is that Bale was a spectacular shapeshifter as always. I enjoyed finally hearing him act in a British accent in the FvF. I don’t care for sports or motor-racing, but I’ll watch anything with Christian Bale in it – or rather I would’ve before I quit watching stuff.

The last thing I watched before I went off the audiovisual medium was The Hobbit trilogy (2012-14). I’d read and enjoyed the book years ago, sometime after watching LOTR. The films start out slow, silly, and repetitive – I felt like I spent an hour watching the dwarves eat Bilbo out of house and home. Also, Martin Freeman’s limited range of acting tics and his bland expression, familiar from Sherlock, grated on me here. I liked the idea of Thorin’s storyline, but it was unevenly paced and didn’t get enough focus; also, his death coming after he picks himself up to do the right thing felt wrong. The movies’ tone is uneven: in the Desolation, the party appears unrealistically and offputtingly dragon-proof. Why the hell would Smaug leave to destroy the town with the dwarves still in the mountain? Legloas and Tauriel are such fantastically efficient fighters that the appearance of five huge armies in the third film seems superfluous: why not just clone this two – you wouldn’t need more than three copies apiece to cut through the orc ranks as a hot knife cuts through butter. Given the apparent invulnerability of the named characters in the first two films, the barrage of deaths in the third feels incongruent. The sets are still beautiful, but now feel more obviously CGI. And unlike LOTR, these films didn’t tie up the storylines neatly, notwithstanding the lower standards of resolution for a prequel. The elf-dwarf lovestory was childish, implausible, and perfunctory, and I’ve have liked to see the Legolas-Thranduil relationship better developed. Most of the secondary characters here felt like exercises in visual design with inadequate psychological stuffing. Some of the fight scenes were interesting, especially Thorin’s boss battle. I fast-forwarded through all three movies and don’t feel like I missed anything.

What I Wrote:

100-word stories: “Vinegar,” “The Doll,” “Afterwards,” “DIY,” “The Plan,” and “Sunday Afternoon.” Writing short stuff is a good tonic for me, picking me out of a slump & getting me into succinct mode, and at one point I planned to write one to launch every day’s writing session. But some microstories became longer stories, and then I found myself diverted from my main writing plans. I’m submitting these micros in a set to lit mags this month, and will continue writing these when I get ideas/when I need a pick-me-up.

“The Rubbish-Van,” a 200-word story. “The Last Laugh,” a 600-word story. These are also ready to submit.

Drafted “Shoes” and “The Gap.” These also came out of microstory ideas, but they’re longer now; will revisit later. My plan was to spend the rest of the year rewriting and editing stories for my short story collection. For new ideas, I’m trying to dump them into my Word doc of notes, and if I end up writing the draft I’m letting it be for now – unless it can be included in the collection and can replace a lesser story – which makes it tricky to decide what to write now and what to write later.

Reread “The Photograph” (2,000 words) which I drafted years ago, and published in Gasher in 2019. Replanned; redrafted. The story’s much longer now (13,000 words), as often happens with me at redraft. Will reread to see if the material & treatment justify this longer length before sending it out for crits. If it turns out the story’s too long for what it is, then I shall be especially disappointed – the whole point of writing microstories to begin the day was to put myself into my hard-to-access members-only Succinct Mode.

Ditto “Love in the Jungle” (7,500) drafted a month or two ago – reread, didn’t like the story: basically a love story, quite straightforward though high fantasy. Modified the story; replanned; redrafted. Retitled “Growing Pains” (20,000). Have already got two crits on this – this needs work. It’s discouraging to spend a lot of time planning, outlining, drafting, and editing, then discover there’re structural problems that demand yet another round. But that’s writing, and that’s why we need crit partners. Shall I get better at writing good first drafts? I earnestly hope so, with practice. I’m continually overhauling and tweaking my overall drafting and editing process based on story-specific feedback, trying to develop a process that’s both effective and efficient. Began replotting this as a shorter, more focussed story.

If “The Photograph” turns out indeed too long, & “Growing Pains” too on my own reread, then I shall rethink my current strategy of developing a very detailed outline: I’ll try just writing down beats (bullet-points of key moments or movements). A beats-outline should help me to keep the big picture always in mind, & thus write shorter as well as more focussed drafts. Or maybe I can treat the long (re)draft as material, and on the next round can simply condense, eliminate, hint, and restructure. I shall try both tactics.

Reread “The Toy Soldier” (7,000 words) from last month; good material, but needs some rewriting for more escalation & continuity (making every event flow from what comes before and cause or inform what comes next). This is a story about obsession, so I also need to develop the intertwining of character and outcome: here the object of obsession acts, in a magic-realist way, on the victim, but always exploits her existing anxieties; the escalation of the obsession in turn intensifies that anxiety. Replotted this story in the final days of the month.

What I Published:

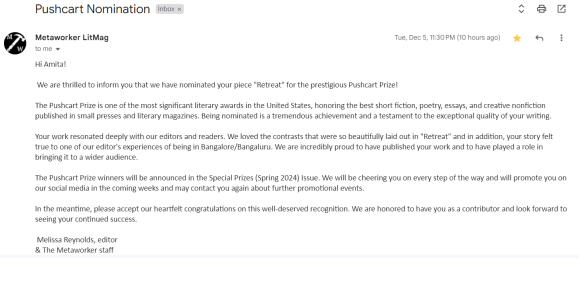

“Retreat” (2,500 words) was accepted for Constellations anthology, to be released this winter.

Got the proofs of “Backsides” (1,000 words) to be published in CEA Mid-Atlantic Journal’s March 2023 issue. Made quite a few minor changes, since my tastes in wording, sentence structure, and punctuation keep shifting.

How was your September? What did you read, watch, listen to, and write? Drop me an email via the contact form.